IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON LIFE

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in in Tampa, Florida, where six talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people to highlight the experiences of people whose lives are being affected by climate change.

As a public radio reporter covering the environment, Jessica Meszaros makes it a point to amplify the voices of Floridians living with climate change. She admits that it’s sometimes difficult to cover a topic like climate change where there is rarely a positive story. But as Allegra Montesano reports, there are reasons Meszaros remains optimistic.

Illustration by Natalia Polanco

‘It’s my job to tell the facts.’ A sustainability reporter balances the ‘gloom & doom’ of climate change and the hope for a solution.

“I understand there’s like this argument that has been built over decades of arguing and challenging science,” said WUSF Public Media sustainability reporter Jessica Meszaros. “It’s not really my job to convince somebody that climate change exists, it’s my job to tell the facts of what’s happening because of climate change, and they can do whatever they want with that information.”

In her decade of working in public radio in Florida, Meszaros has covered many stories about climate change. She’s not only seen the divisiveness of the topic, but also the effects on the state and its residents.

On her beat, she explores the effects that the crisis has on Tampa Bay area communities, frequently interviewing scientists and other experts about developments.

Listen: 'It's my job to tell the facts.'

Jessica Meszaros investigates water quality with a group of scientists (not pictured) at Telegraph Creek near Fort Meyers, Florida in 2016. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Meszaros)

In 2015, Meszaros covered a panel on ocean acidification at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium in Sarasota. She said the frustration of the presenters — with some scientists being moved to tears — struck a chord with her, showing her for the first time how difficult addressing the problem is.

“It made a really big impact on me because the scientists seemed so tired,” said Meszaros. “They seemed so afraid of the future and tired of nobody listening to them and talking about how when they bring up climate change or what was going on, people’s eyes would glass over and they became disinterested.”

Meszaros is committed to amplifying the voices of everyday people who have their own concerns about the subject.

“I’ve heard from some people about the nature that they’re finding or not finding any more in the water,” Meszaros said. “I’ve heard from people discussing how it affects, in particular, people of color and poorer communities, and because of the urban heat island effects and the fact that maybe there are less trees and there is more flooding in these areas.”

De’Andre Long is one of those people who shared his story with Meszaros. He lived in Tampa for 30 years without a car, so he spent much of his time as a pedestrian. He also worked a number of different jobs outside, such as construction and at a patio bar, so he knew firsthand how much hotter the area has gotten over time.

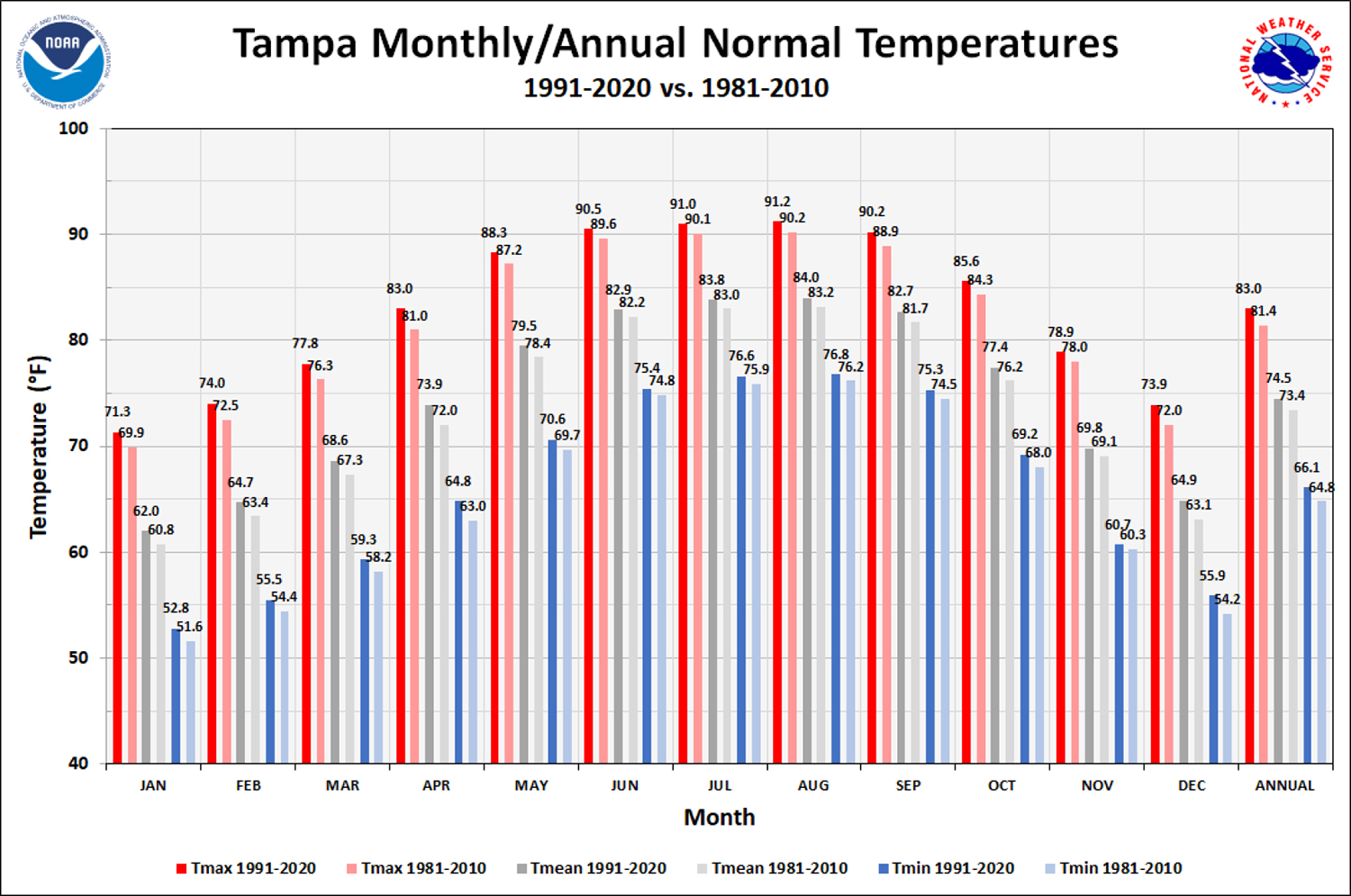

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the annual average high temperature for Tampa between 1981 and 2010 was 81.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Between 1991 and 2020, that average climbed to 83 degrees.

Having grown up in South Florida, Meszaros says climate change has made itself apparent to her in many forms as well. Her family home in Kendall in Miami-Dade County was in an area that was once lush and swamp-like, the streets covered in frogs and snails even after a light rain. What was once a neighboring forest is now a busy road devoid of wildlife.

“Now knowing what I know about climate change, I understand that the more that we develop and the less green space that we have, the worse climate change and global warming is going to be because we are contributing to that urban heat island effect.

“And we know when we develop that we’re losing trees that grab carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and we’re losing that green space to keep it cooler in the surrounding areas.”

Comparisons between the monthly and annual temperature highs and lows in Tampa from the previous 30-year averages and the current ones show that the city continues warming up. (Chart courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Jessica Meszaros interviews biologist Jessene Aquino-Thomas, who helped develop artificial mangroves in Manasota Key in 2017, where marine life is slowly beginning to flourish again. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Meszaros)

Meszaros says hearing the personal stories of “real people” is vital to understanding the situation, especially for those who may not be affected the same way or who challenge the existence of climate change.

“Being able to share those stories has been the highlight of my career so far because it feels like you’re giving a voice to the community,” she continued. “I feel like it’s just a different side of climate change, rather than just talking about data and the numbers, you know, hearing from real people.”

“How can you challenge somebody’s personal experience?”

“Learning about climate change has truly changed my life because it has helped me to understand how I live my life and given me an awareness about what I do every day and how that might affect the planet, and how it might affect the future for my future family.”

Observing nature, camping and kayaking are some of the activities Meszaros enjoys in her free time. She says those experiences help her understand her work better.

“The squirrels running around in the trees and the particular birds and you can hear the river otters, but you can’t see them, or kayaking past an alligator’s den, you know, just really amazing parts of Florida that I feel like it helps to inform my reporting and keep me centered as to what we’re talking about, so it doesn’t become like this outside theory. It’s very real for me.”

Meszaros admits that it is sometimes difficult to report on a topic like climate change where there is rarely a positive story.

“Talking about that gloom and doom isn’t necessarily healthy and accurate. There are solutions, there are things that can be done,” she said. “If you want to look far into the future, a few decades, I think there’s going to be a lot more firsthand experiences to report on climate change, unfortunately.”

Despite those concerns, Meszaros remains optimistic about the fact that there are people who are dedicating their lives to trying to find solutions.

“When I saw the teary-eyed scientist talking at Mote Marine Laboratory back in 2015 and how passionate he was, I realized that there are people who see this every single day, it’s their lives, and you can’t turn away, and now I get it because I’m looking at it through that lens in my reporting,” she said.

At 21-months-old, Jessica Meszaros searches for Easter eggs in the backyard of her Miami-Dade County home in 1992. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Meszaros)