IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON LIFE

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in in Tampa, Florida, where six talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people to highlight the experiences of people whose lives are being affected by climate change.

Elizabeth Eubanks has been the lead gardener at “From the Ground Up” community garden for six years. Before that, she taught science for about 20 years. She intertwines her gardening and educating skills to teach members of her community how to grow their own food as climate change and food insecurity threaten the food supply.

Illustration by Natalia Polanco

Climate Change is Impacting Food Production. This Is How One Pensacola Gardener is Fighting Back

Former school teacher Elizabeth Eubanks brings her classroom skills to a community garden where she educates students and volunteers in how to harvest their own food, a form of resistance against extreme weather patterns and food insecurity.

“I invite people to really think about whatever their meal is and really think about how many hands have touched it,” Elizabeth Eubanks, lead gardener of “From the Ground Up” community garden said. “Because if I let you harvest your collards right here and right now, and then I go, grab some garlic for you and some herbs and you go home and cook it, that’s one pair of hands. The carbon footprint is reduced and you know exactly where your food came from and what pesticides are on it or not.”

Eubanks has been the lead gardener of “From the Ground Up” in Pensacola, Florida for over six years. From seed to dinner plate is a process that Eubanks enjoys teaching to members of her community, welcoming all ages to learn how to grow their food.

During the week, the garden is full of eager community volunteers, not afraid to get their hands dirty as they learn the ins and outs of harvesting.

“We always need to weed, seed, plant and harvest,” Eubanks said. “That’s the continuum… and then recruiting people and bringing them in. So I’m on social media every day, posting hours for the garden and then when the volunteers get here, leading the volunteers. So sometimes I may not get my hands dirty at all, but sometimes that’s all I’m doing.”

The 172 x 160 foot garden located just under Interstate 10 in Downtown Pensacola is full of fruits, vegetables and herbs.

“It’s winter and our brassicas are in full bloom. We have collards everywhere, we have herbs like dill. The weather has been unseasonably warm, so we still have peppers in the garden, which could be unusual for a regular winter in Zone 9A. We have lots of lettuces, we have roots and carrots and radishes and beets and turnips all started. We have my favorite thing, mirliton, and that is a vegetable. The heirloom variety is called Papa Sylvest, and it came from New Orleans, which is my hometown.”

LISTEN: 'We always need to weed, seed, plant and harvest...'

Elizabeth Eubanks holds her favorite crop, mirlitons. The heirloom variety is called “Papa Sylvest,” a vegetable native to New Orleans, her hometown. Eubanks spends anywhere from 10 to 50 hours in the garden per week, depending on the season. (Photo by Sierra Lyons)

The garden’s number one rule, “Do no harm,” is boldly plastered at the entrance of the 172 x 160-foot garden. The space is also a venue for community events such as concerts and art markets. (Photo by Sierra Lyons)

Since stepping into her role, Eubanks had taken pride in starting her own seedlings. But after an unusually wet September and October, her seedlings were over-saturated and she had to purchase plants for the first time.

Hurricane Ida swept through the eastern United States in August and September 2021. And although Pensacola was not directly hit, it did leave minor damage to the garden, downing some of their trellises. September and October were two of the rainiest months of 2021 in Pensacola, according to precipitation records from the National Weather Service.

“I came into work one day and the banana trees, half of them, had fallen, and that had never happened before. We’re in Hurricane Alley…I think having multitudes of hurricanes is something to consider.”

With extreme weather patterns increasing globally, gardening is a form of resistance and protection as climate change impacts food production.

Before she was the lead gardener, Eubanks taught science in Palm Beach County for about 20 years to students ranging from elementary to high school. Pensacola became her place of rest when not teaching, and after strolling past the garden on her daily walks, she began volunteering. After three months, she was asked to step into her current role and she happily obliged. Her bachelor’s of science degree in zoology and master’s degree in education makes her a well-rounded candidate for not only running a garden but also teaching volunteers with varying skill levels.

“When I think about some of the people here that I love to work with, it’s at-risk families or already stressed families. So if they’re already insecure with where they live or if they have food insecurities or clothing insecurities, anything like that is just going to get a lot bigger as time goes on. The more that I can educate people, I can educate you. Then you’re going to hopefully take that out into your community or you’re going to tell people and come learn from the garden.”

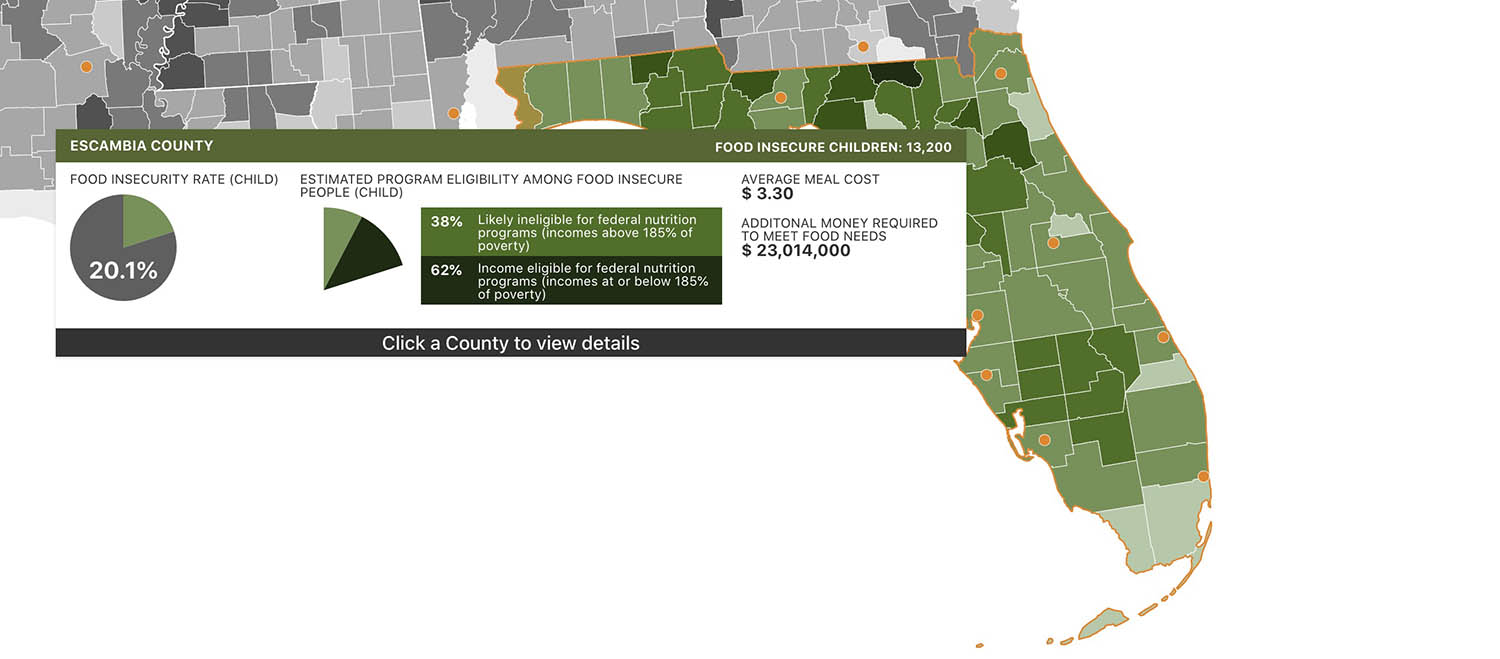

According to Feeding America, Escambia County, where Pensacola is located, had a child food insecurity rate of over 20% in 2019, according to data from Feeding America. That results in 13,200 or 1 in 5 children going hungry in the county. (Infographic courtesy of Feeding America.)

As droughts, extreme temperatures and high CO2 levels impact crops for major farms in the United States, residential gardening is a means of survival. Eubanks says preparation is her best defense against climate change because extreme weather conditions will only increase as time goes on.

“I get educated and share with youth and teach them how to educate. I stay actively involved with groups that I have participated in: teacher-researcher experiences with like NOAA Teacher at Sea, PolarTREC, and Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) Earth Programs. I also lead youth into creating their own research projects in order to present at these conferences in a professional manner. They become empowered advocates for our planet and get to present to peers and professional scientists.”

Eubanks encourages students to bring their newly gained knowledge back to their communities.

“I want people to travel, I want them to see the world, I want them to get out there. But at the same time, not to be a conflict of interest, I want them to focus on what’s in their community and buying local, supporting local people.”

Orange trees are in full bloom at the back of the garden. “From the Ground Up” has a variety of produce and flowers such as cabbage, turnips, dill, bananas and coneflower blossoms. (Photo by Sierra Lyons)